The Real Legacy of 9/11

As we have done every year for the last 22 years, we spend today mourning the losses of the innocent, cherishing the heroism of our first responders, and reflecting on many stories of individual heroism. Who can forget the heroes of Flight 93, all passengers and crew, who rose in rebellion against their captors, successfully diverting the plane away from its target at the cost of their own lives?

9/11 gets less and less mention as every year goes by. For those who were there, images of the brutal terrorist attack are seared into their psyches. For me, the tragedy could only be shown through VHS tapes, history textbooks, and photographs. It is as historical to me as the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the attack on Pearl Harbor, and the American Revolution itself. As time goes by, fewer and fewer people will have personal memories of 9/11. This will make it more difficult for people to understand the impact of the attacks and the deep emotions that they evoke.

For those who are older, it is sometimes astonishing to realize that this horrific attack was two decades ago. Many believed the attacks were a watershed moment that would usher in a new era of global conflict. Was it to be a new era, as so many believed, or was it merely the final chapter in the already concluding Cold War?

Mona Charen, writing for The Bulwark, theorized that:

“This enemy was in some respects like our old enemy, communism. Islamism was a coherent worldview. It had global ambitions. It provided existential certitude. Like communism, it disdained pluralism and freedom of thought and expression. It ruthlessly suppressed dissent. In some ways it was therefore a familiar adversary. It felt like the latest despotic, fanatical ideology to challenge us, following fascism and communism.”

As Mrs. Charen so eloquently put it, 9/11 was merely the continuation of the global struggle between Western democracy and Islamic extremism that emerged during the Cold War. It was no new era, but instead the last hurrah of a piece of history. Any present-day discussion of our subsequent foreign interventions, the policy changes after, or even the attack itself, now have the same relevance as other historical events. Obviously, history is still worth scrutinizing and analyzing. However, these policy debates have little effect on contemporary America, as evidenced by their recent lack of prevalence in our political discourse.

The Global War on Terror did not turn out the way many had hoped. The scope was too broad, the enemy unknown, and victory had no parameters. Defeating radical Islam was impossible; one cannot wage war against an idea. The true war against extremism was not to be won on battlefields, but in a battle of belief. Religious conflicts have been a staple of the history of human civilization. Unfortunately, this has simply always been the way of civilization. Liberalizing the Middle East? President Obama's inaction in the Arab Spring burned any prospects of that coming to fruition.

Iraq, and its valuable oil reserves, have fallen under the sphere of influence of Iran, arguably our greatest geopolitical adversary in the region. Awash with weapons and militias, there is a growing risk of sectarian conflict. Iraq remains on the brink of a Shiite Civil War. Our work in Afghanistan to give healthcare, democracy, education, and overall better prospects for their children's future has been wiped away. Afghanistan is once again ruled by the Taliban, an overzealous, authoritarian, and brutal regime. It is highly likely that it will return to its previous role as a safe harbor for terrorists.

But the most important lesson from September 11th was summarized by President Bush:

“Terrorist attacks can shake the foundations of our biggest buildings, but they cannot touch the foundation of America. These acts shattered steel, but they cannot dent the steel of American resolve.”

It is truly hard to conceive what went through George W. Bush's head on this ill-fated day. Seven months into his presidency, Mr. Bush was on his way to Emma E. Booker Elementary School to read to a group of second-grade students. It was an ample opportunity to discuss his administration's intentions for federal education reform, and a touching visit from the President never fails to delight a group of school children.

As he sat in Room 301, reading with the students, Andy Card, then-White House Chief of Staff, briskly walked over and leaned into his ear. "A second plane has hit the second tower," Mr. Card whispered. "America is under attack." The president reacted as best he could.

Slowly nodding, he did nothing to rouse any panic. He continued to listen to the children's stories, praised their reading, and took some photographs with them. Then, the real work began.

His behavior may have seemed erratic at the time, if not for the sheer unprecedented nature of the circumstances. He was flung from one Air Force base to another as more and more information kept piling in. In the confines of Air Force One, Mr. Bush and his team could only catch TV when they flew over a city with a good signal.

Most CEOs live by a rule popularized by Jeff Bezos, that decisions are made with around "70 percent of the information you wish you had". Being President is no different. Mr. Bush's response to 9/11 is a prime example of the rigors of decision making in the middle of a serious crisis. In the pre-social media world, information about the attacks was limited and the President's decisions had to be made on the fly.

Mr. Bush did make his most important decision on that day: returning to the national capital to address a frightened and shocked nation. In one of the most impactful and influential addresses from the Oval Office, he stated that "We will make no distinction between the terrorists who committed these acts and those who harbor them." A few days later, he phoned then-New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani, reporting that "my resolve is steady and strong about winning this war that has been declared on America."

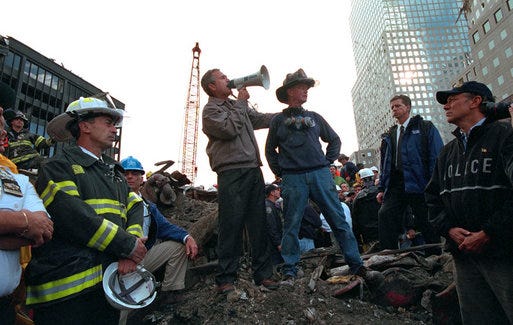

Following the attacks, on September 14th, President Bush, accompanied by Governor George Pataki and Mayor Rudy Giuliani, visited "Ground Zero." This moment was recounted by President Bush in his memoir, "Decision Points."

“When the workers saw me, a line formed. I shook every hand. The worker’s faces and clothes were filthy. Their eyes bloodshot. Their voices were hoarse. Their emotions covered the full spectrum. There was sorrow and exhaustion, worry and hope, anger and pride. Several quietly said, “Thank you” or “God bless you” or “We’re proud of you.” I told them they have it backward. I was proud of of them.

After a few minutes, the mood started to turn. One soot-covered fire-fighter told me that his station had lost a number of men. I tried to comfort him, but that was not what he wanted. He looked me square in the eye and said, “George, find the bastards who did this and kill them.” (p. 148)”

Mr. Bush then proceeded atop a mound of metal, a melted fire truck. This was unlike most presidential addresses. There was no podium, no microphone, and no teleprompter with pre-selected words designed to elicit a variety of reactions. Just a man, and the people he was pledged to serve and protect.

He raised up a bullhorn and began to console. Though, as he spoke about how America was on bended knee in prayer, many in the crowd lamented that they couldn't hear him. "I can hear you!" he shot back. A cheer erupted. "I can hear you. The rest of the world hears you," Mr. Bush continued, amidst roars of approval from the crowd. "And the people who knocked these buildings down will hear all of us soon!" Chants of "USA, USA, USA!" filled the air like a lion's roar.

As he rode down the West Side Highway, George W. Bush was surprised to see so many people waving American flags and cheering him on. "I hate to break it to you, Mr. President," Mayor Rudy Giuliani told him. "But none of these people voted for you." It was an odd sight, indeed, for New Yorkers to cheer a conservative Republican, especially one who had lost the state by a margin of twenty-five percentage points just ten months earlier.

And then life went on. Mr. Bush recalled in his memoir how:

“Most Americans returned to life as usual. That was natural and desirable. It meant the country was healing and people felt safer. As I record these thoughts, that day of fire is a distant memory for some of our citizens. The youngest Americans have no firsthand knowledge of the day. Eventually, September 11th will come to feel more like Pearl Harbor Day — an honored date on the calendar and an important moment in history, but not a scar on the heart, not a reason to fight on. (p. 150)”

He concluded that:

“September 11th redefined sacrifice. It redefined duty. And it redefined my job. (p. 151)”

Not since Franklin D. Roosevelt has an American president had to deal with an attack on the homeland. Mr. Bush brought something to the occasion that few presidents now can emulate. At a time when outrage could have been harnessed to appeal to nativism and prejudice against Muslims, our president did not stir those fires, and neither did the people of our country. In comforting the nation, Mr. Bush brought a unity that has not been severely lacking from his successors.

So, even though it took a national crisis, the spirit of America is strong. Our institutions stand firm, our resolve is impenetrable, and our shared values ultimately prevail despite any polarization and differences of opinion. The biggest legacy of September 11th is that love of country and of each other triumphed over any partisan bickering when it could have been so easy to give into fear and isolation. That is the America that is always worth fighting for.